Tulips, Tessellation, Translation: The Ethos of Harmony

The photograph before me is from a summer morning in 1982, from an album of that year’s Eid ul Fitr congregation. Taken with our very basic snapshot camera, the Kodak Tele-Instammatic 608, it lacks the sharpness and vivid colours we are so used to now, in 2020, but this photo is a special one, for two reasons: it is an image of the great Muhammad Ali Clay who was present for Eid prayer in the Islamic Center of Los Angeles, and because it was my first ever visit to an American mosque, at age 9. Enveloped in the tranquil beauty typified by Islamic floral-geometric design, I found myself at prayer in a hall with people of all ethnicities, ages, countries of origin and skin colors. In later, more turbulent years, this image of festive beauty infused with a sense of peace and elation, blurred as it may be, would remind me that it was here that I received, in essence, my most important lesson, that no matter the place or moment, sacredness comes from diversity in meaningful convergence and that the true aim of civilization is to build by integrating a wide array of the finest influences, to preserve and develop the best ideas of the past that promise to carry us forward, to collapse distances not only in time and place and disciplines, but between human beings.

To collapse distance, is to be a bridge. The people of ideas I admire the most have one thing in common: making bridges, so to speak, between apparently disparate realms—science and art, faith and reason, geometry and aesthetics, mystic poetry and pharmacology, astronomy and gemology, medicine and political philosophy, architecture and ecology, physics and music theory, the sacred and the secular, the “East” and the “West.” This approach of studying multiple domains and making connections without presuppositions and prejudice signifies an open-mindedness that is key to true investigation, and, in most cases, paired with a unique tolerance for a divergent origin or point of view, enabling the thinker to chance upon brilliant discoveries simply by reaching across to other modes of thinking, traditions, cultures and historical periods. Inherent in the Islamic concept of “ilm” or dedicated pursuit of knowledge, is the spirit of harmony— exploring the infinite bridges between diversity and unity, which lead up to the values both Islam and America have in common: pluralism and creativity.

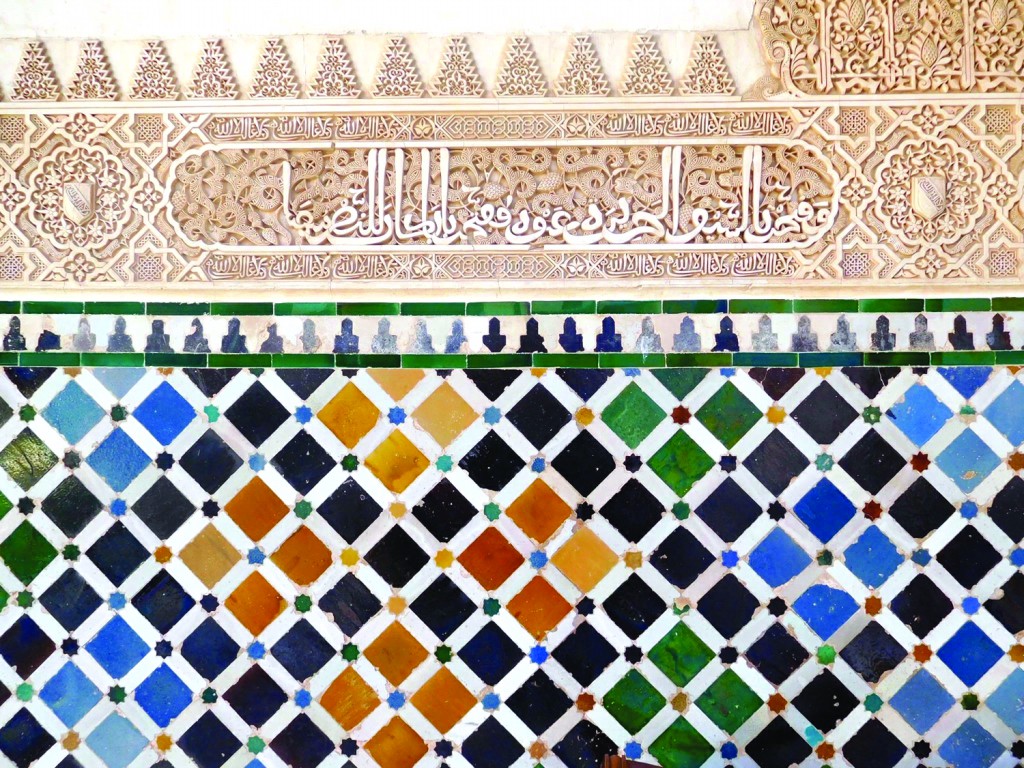

Going back to that blurred photo from 1982 which happens to speak so lucidly of our living values of celebrating oneness while honoring diversity, I’m reminded that God himself has 99 names denoting diverse attributes which may seem contradictory but are unified. He is “al-Baseer” the “all-seeing” as well as “al-musawwir,” “the fashioner” or “the great artist.” If the physical act of seeing represents empiricism, science and reason, imagination represents the realm of innovation and creativity, the enterprise of spirit such as the fine arts. These two realms have often been perceived to be at odds with one another but the study of the Islamic civilization shows us that it is possible to collapse the distance between them and find growth in the connections. One of the primary examples of this is the tradition of using geometry as an aesthetic language; across the Muslim world one finds geometric designs in architecture, metal-work, fabric, glass and artifacts both decorative and of common use, made in myriad other materials. Hexagons, concentric circles and other overlapping shapes, precisely measured and repeated, are universal and extrapolative: the mind deciphers this logical language as spatial reasoning. Add to that geometric gesture, variations of color, scale and texture, and you have a work so elaborate, so beautiful in its parts and as a whole, that it becomes more than merely ornamental— it invites reflection, piques a sense of wonder. The effects of “tessellation”— produced by dividing the plane into multiple tiles with no overlaps and no gaps and commonly used in Islamic art— had such a great impact on the Dutch artist MC Escher when he saw the tiles of the Alhambra in Spain that he drew 137 prints in response, including some of his best-known works.

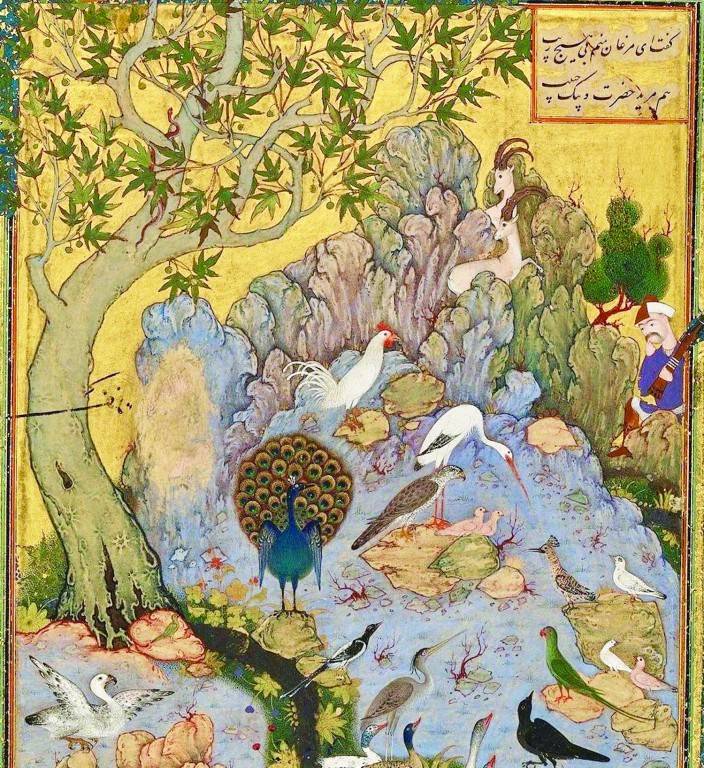

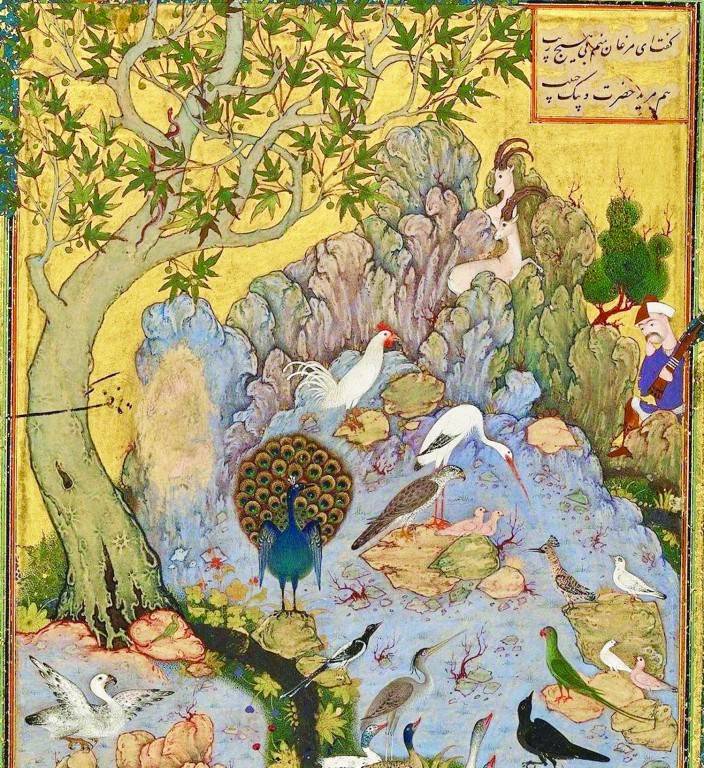

My favorite Escher drawing, inspired by curvilinear, fluid triangles in the Alhambra, is of interlocking birds. Even though there is no direct connection, the image of wings outstretched in unison recalls “The conference of the Birds,” the Sufi masterpiece by the Persian poet Fariduddin Attar. In the original title of the poem “Mantaq ut Tair,” the Arabic word “Mantaq” stands for language so precise and subtle that it makes logic transparent. Attar the venerated 12th-century predecessor of Rumi, based his parable on the Qur’anic description of prophet Solomon’s ability to understand the language of the birds. By way of telling a story about a journey that birds of different kinds take to reach the mythical king-bird Simurgh, the poem delves into the challenges of the mystic experience. Not only does the story have its origins in the deep reservoir of symbolic material in Solomon’s story which has been explored imaginatively in numerous works of Muslim literatures throughout history, it elucidates the ultimate message. In Attar’s story, the birds must fly as far as China. He says:

“It was in China, late one moonless night, The Simorgh first appeared to mortal sight”

China, as used here, is not the land we know as China, but the symbol of mystic experience, as inferred from the saying of the Prophet (pbuh): “Seek knowledge; even as far as China,” implying that an illuminating truth can be found anywhere— pursue it fearlessly, with perseverance and without prejudice.

Embracing this idea of valuing knowledge, no matter the source, places such as Fez in Morroco, the legendary Al Andalus or Muslim Spain, and most importantly, the Bayt ul Hikma or “House of Wisdom” in Baghdad, became hubs of translation and transmission, bringing all the great works of Greek into Arabic and from Arabic to Latin, functioning as a bridge between important languages of antiquity, adding original works, and becoming a catalyst of modernity as these works were later carried over into the Romance languages and introduced all over Western Europe. Awash in translation, knowledge from diverse sources in the East and the West illuminated and transformed the world. In tandem with this, Muslim scientists made key contributions in developing scientific and mathematical theories and technological inventions that had originated in different parts of the world, most notably in ancient Greece. Among the myriad examples ranging from medical sciences to physics, geometry to astronomy and chemistry, is the development of the camera itself. Following the work of Aristotle, and others, Ibn al Haitham was able to integrate his study of the eye, with the existing studies of light, to come up with a breakthrough in building the first working camera obscura. This rudimentary version of the camera was not used to generate images but to understand optics. By inventing the camera obscura, the precursor to the pinhole camera, Ibn al Haitham successfully demonstrated how the eye functions, and pushed further the developments in camera design and function.

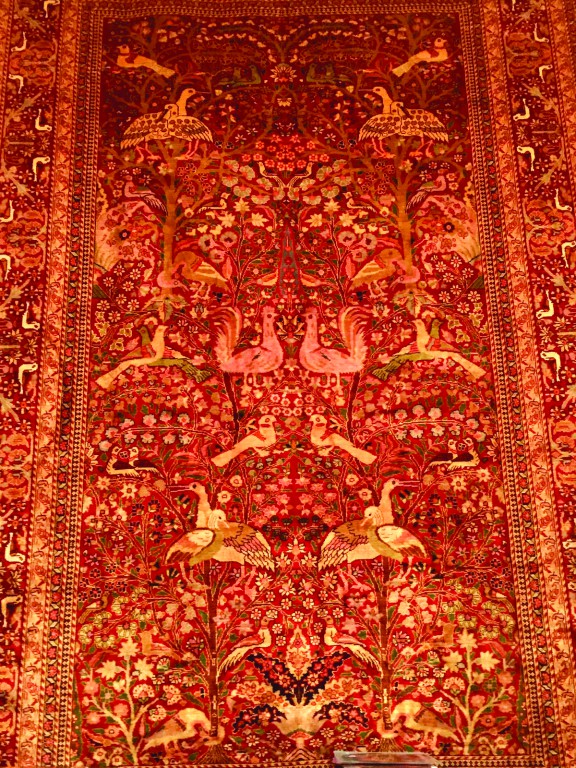

In our historic moment, cameras have become indispensable as seeing, recording and communication devices, used everywhere from satellite technology and research in space to surgery and surveillance. The camera collapses distance; it makes the past present, the unknown better known, it’s an eye that can see accurately, but it’s also a tool for the imagination, said to have been used as an aid to artists such as the 17th century Dutch master Vermeer, who used the pinhole camera to project what he wanted to paint. He was living in a time when ideas were being borrowed across disciplines and cultures of the East and West like never before, a time of empire and material efflorescence. Thanks due in part to what we call the Silk Routes, a vast network of land and sea routes across the topographically diverse stretch from East Asia to Western Europe and North Africa— an area that traversed the Muslim lands—new currents of confluence transformed the cultural, economic and political contours of the world. Though conflict is also an unfortunate outcome of empire and is inseparable from the human story, the access that the Silk roads provided, gave rise to cultural encounters that changed the course of history for the better. Among these, there’s one that not only speaks of collapsing geographical distances, connecting faraway corners of the earth, but also of the connections between domains as far apart as aesthetic trends, spiritual sensibility, a wide spectrum of arts and crafts, politics and economics. Most of all, it speaks volumes about beauty as a sacred language for Muslims. It is the story of the tulip, the flower that the Seljuks brought from the foothills of the Himalyas, likely from the land of Kashmir, to Turkic areas across Asia. The tulip’s unique richness of color and elegant shape took the flora-loving world by storm. It found a place in Persian-, and subsequently Turkish- and Urdu poetics, especially the verses of the great Sufi poets. The letters that spell “laleh,” the word for tulip, are the same as the letters that spell Allah, and the shape of the flower, especially to the mystic’s eye, appears to form the shape of the word Allah. It became a symbol of devotion to the divine. The flower became more and more popular as it was absorbed in a flourishing symbolic, delicately-wrought language of Islamic arts—crafted as calligraphy, woven and embroidered on fine silks, engraved in silver, gold and copper, etched on ceramic tiles— cut in cabochons and faceted gems— the tulip became the royal insignia of the Ottomans, cherished as a symbol of divine grace upon the vast empire covering most of the Mediterranean coastline, Turkey, the Balkans, the Caucuses, Iraq, Arabia and much of North Africa.

Here, the story takes an interesting turn: due to the tulip’s regal association with the wealthy Ottoman empire, the flower became first an exotic object of interest, then muse to the Dutch Golden Age Artists, then a sought-after commodity, and finally, a commercial fetish of epic proportions, in the 17th-century Netherlands. The phenomenon, which came to be known in history as “Tulip Mania,” is considered the first recorded speculative bubble, where the contract value of a tulip bulb steadily rose until at one point it became even higher than the value of a house, and then it collapsed just as dramatically. Economic disaster notwithstanding, the unprecedented global fuss over a simple flower that had begun in central Asia with the evolution of a distinctive lexicon—the tradition of Islamic contemplative arts— transmuted into a wholly different but nonetheless remarkable art scene: paintings of tulips and portraits of aristocrats wearing tulips were commissioned widely, and became a permanent feature of the Dutch golden age. To this day, the tulip flower is the pride of Holland’s horticulture industry and is a major export commodity, and Dutch paintings of tulips are known the world over.

The aesthetic language which developed around the tulip in the Islamic world not only communicates the complex relationship between nature and art, trade and politics, governance and spiritual expression, but also the instrumental role played by the many Muslim cultures along the Silk Roads, in passing on ideas in all geographical directions, and cultivating a richly varied yet cohesive artistic idiom. From Kashmiri shawls, to Turkish ceramics, architectural motifs in stone and woodwork to copperware, jewelry and tea glasses, in calligraphy and poetry from Muslim cultures cross Asia, the tulip has remained a beloved symbol of divine harmony for a near-millennium and continues to be one even today.

Besides tulips, tessellation and translation, there are countless other examples that are equally emblematic of the ethos of ilm, the principle of harmony, and the spirit of collaboration in enduring works of the Islamic civilization. These are contributions that changed the world for the better, contributions such as new irrigation techniques and crops, cartography and navigation, paper manufacture and book arts, advances in medicine and invention of surgical instruments, astronomy, geology, musical instruments, architectural design and urban planning—the greatest contribution of these being the sustained, healthy relations with diverse communities during a significant span of Muslim rule, be it along the thriving, multi-religious and multiethnic cultures of the Silk Road or the legendary “convivencia” of al Andalus, which brought together three faiths and three continents in a shared golden age.

At my first Eid congregation in a mosque, I may have been oblivious to the complex finesse of vegetal-geometric patterns in the mosque, the aura of contemplation produced by the subtle aquamarine tiles, the measured melody of the Qura’anic recitation, the embodied unison of prayer, and even the snapshot camera that captured the faces of family, but the effects of peaceful celebration pillared by these gestures of harmony have stayed with me as a cherished memory, whetting a lifelong appetite to learn more. The message underlying the ethos of harmony is an urgent one, and it is that we exist only in relation to one another, and truly thrive only when we honor what connects us.

The article was originally published on The Friday Times.

Post Tags :