Visiting Rumi’s Tomb In Konya

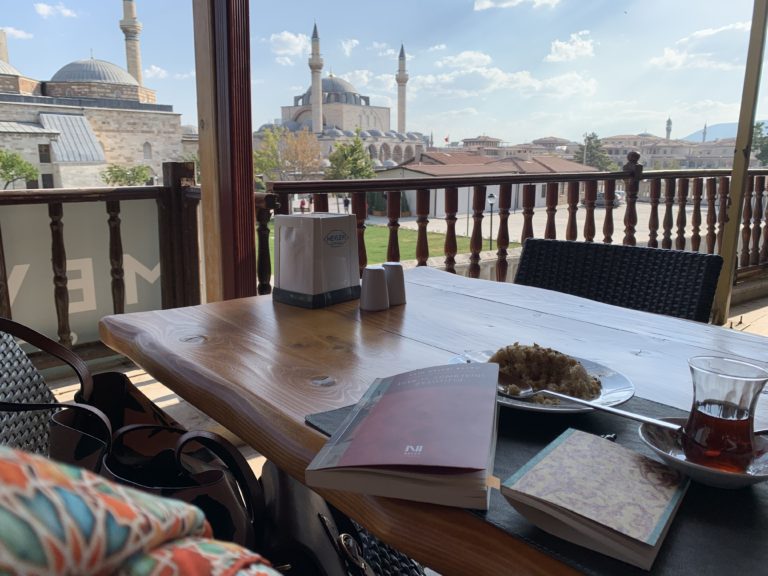

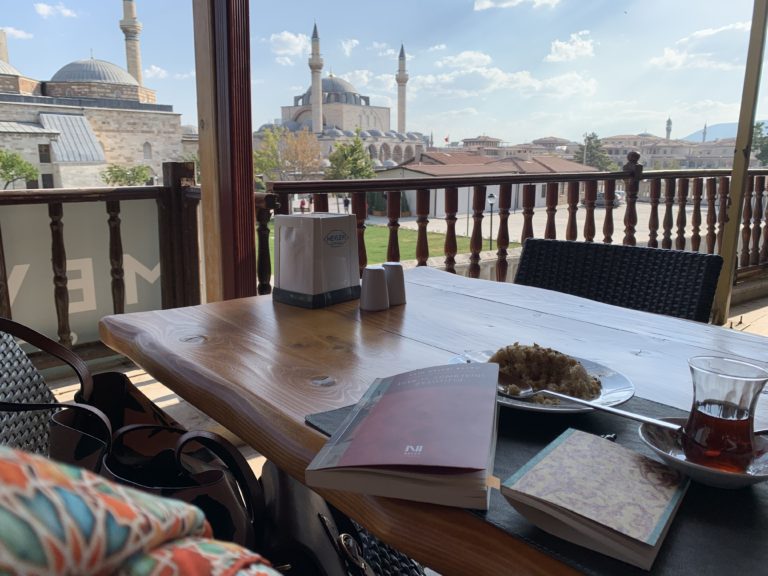

At dusk, the shaft of light striking Rumi’s tomb is emollient as pale jade. It has been a long, hot day in Konya, I’ve been writing in a café-terrace overlooking the famed white and turquoise structure of the tomb-museum complex. I sip my tea slowly, facing the spare, elegant geometry of the building that appears as a simple, intimate inscription on the vast blue. For once I am studying Rumi’s verses in Persian, not repeating English translations or paraphrasing in Urdu. “Bash cho Shatranj rawan, khamush o khud jumla zaban,” “Walk like a chess piece, silently, become eloquence itself!” I’m reciting to myself in the din, in awe of the kind of magnetism that would pull one as a chess piece. Only the heart understands this logic, not any heart, but the one that has been broken open, the one that is led to the mystery in cogent silence.

For once, I am letting the music of Rumi’s diction guide me: “khamush” (silent) and “khud” (self), a sonic coaxing of paradox, two words beginning with the same consonant, the first ending in “sh’, a sound that evokes the hushing of the ego’s voice, the softly-fading whisper of self-annihilation, the second ending as a sonic anchor in “ud,” suggesting the triumph of the self as it sheds worldly desires, alchemizing from base to the gold it was meant to be. This meditation yields the word “khuda” or “God,” who is paradoxically both “closer than the jugular vein” and a “hidden treasure,” in the words of the Qur’an, to be revealed actively, painstakingly in the hidden recesses of the self– as Rumi and the Sufi tradition teach. The divine resides in the self’s silences and music, solitude and communion, longing and ecstasy. Rumi’s path to love passes through such paradox; to be a Darwish, is to “linger by the door,” content to make a home of the beloved’s threshold where he gives himself up to gnosis through praise.

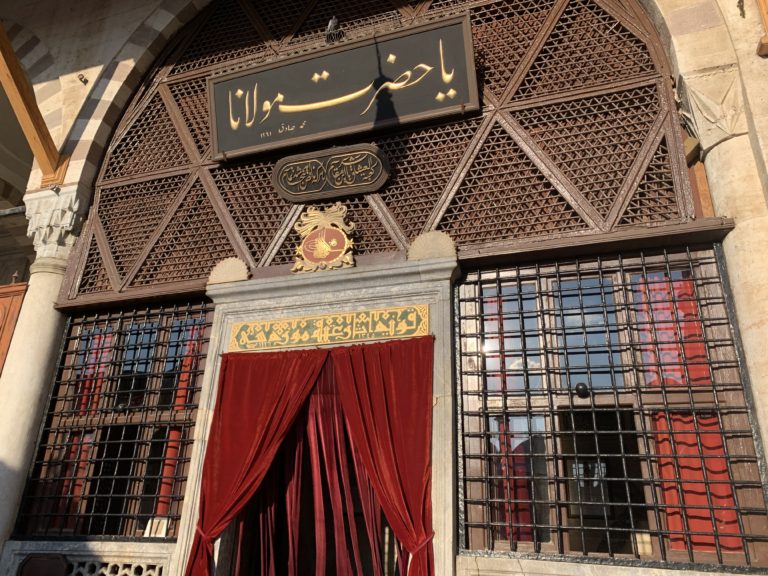

Of the many doors to enter Rumi’s tomb/museum complex, I enter by “Baab e Gustakhaan,” “The Door of the Irreverent ones.” I recall the instances of irreverence in the Mathnavi, that boil and distill as teachings of the ultimate sublime, instances in which it is the crassness of the parable that illuminates the ego’s peculiar pettiness; descriptions so visceral and crude that they serve to scrub the soul clean.

The door that I go through is simple, as are the buildings of the museum and the tomb. The sight of the bright russet velvet curtains at the entrance of the tomb makes me smile; isn’t it irreverent to give a celebratory color to what is conventionally deemed a place of mourning? By Sufi logic, death is something to celebrate, as it marks the end of the ego’s battles and the beginning of union with the divine as a mature soul. I gaze at the threshold and the curtain for a while, taking in the joyful color of the curtain and recalling Rumi’s verse about how language slips like a donkey in mud when it comes to love. Mortality is at once a matter of pity for our ultimate helplessness and a matter of delight because it allows us to return home to the beloved.

As I sit by the threshold to cover my shoes with the plastic covering we are asked wear before entering the tomb, I feel the energy of the other visitors. It takes me a while to notice faces and outfits or to make guesses about where they might be from because they exude a familiar vibration. Some wear headscarves, many do not, some carry prayer beads, some are fashionably dressed, others plain. I hear many languages and recognize some of the cultures, but I’m not paying attention to specifics; instead, I’m savoring the tacit fellowship of the moment. It is as much a gift as being present here. Wasn’t this the cosmopolitan scene, 800 years ago, at Rumi’s funeral too? An assortment of humanity from numerous ethnicities, faiths, domiciles and languages, joined by the message of purifying the spirit with love.

The main hall of the tomb feels like a festival; it is sublime without being somber. I have never been surrounded by so many graves and witnessed the sense of camaraderie and love, a love that is elevated by Adab or the expression of sincere respect that is the hallmark of Mevlevi Sufism. Immediately prominent as I enter the tomb building is the mural design on the far wall which reads “Al Baqi,” the “Eternal One” or the “One who Remains;” it is one of the 99 “Asma al Husna,” or “Beautiful Names of God.” Written as a colorful mirror image calligram, “Al Baqi” is a reminder of the temporariness of our earthly existence.

Rumi’s family members and many fellow-Sufis are buried here side by side. On each grave is placed the turban of the deceased wearer, a custom which may be a symbol of leaving worldly status and identity behind, reminiscent also of the dervish’s cap which represents the tombstone of the ego, an embrace of “heech” or the exquisite nothingness which leads one to “become prayer itself,” to discover the divine within as a result of burying the ego, to know this love for the One as an all-consuming passion that is inextricable from loving all beings at all times.

The framed calligraphy pieces on the walls give the place the look of a family graveyard where decorations have continued to be added as graves are added. The carved and intricately painted ceiling and pillars around Rumi’s grave have springtime hues such as saffron, orange, green and gold: beautiful, uplifting hues. The green sheet that covers Rumi’s grave has a verse from the Qura’an that reads “Friends of God are not overcome by sadness or fear.” The sound of the ney flute in the distance, Rumi’s central metaphor for yearning to reunite with the divine, enters as part of the sentiment of this place, the paradox of devotion enhanced by separation and the joy of finding the beloved within.

This neighborhood of Konya is made sacred by love and remembrance taught by one who proclaimed himself “heech,” after attaining and rejecting all manner of worldly success as a scholar, happy to be a “chickpea” or ‘door-knocker” as long as he was engaged in praising the divine beloved. I am dumbstruck by the sheer beauty of the sentiment, realizing that the visit to Rumi’s tomb is not about Rumi at all. It is about being bathed in the language of love and recognizing the divine within the subtle signs and deep silences of that language. The door I choose to pass through on my way out is “Baab e khamoshaan,” the door of the silent ones.

The article was originally published on 3 Quarks Daily